Chickadee Birch Beer

Returning now to fictional goods and services; try a Chickadee All Natural Birch Beer.

There are seven species of chickadees in North America: the Black-capped Chickadee, Boreal Chickadee, Carolina Chickadee, Chestnut-backed Chickadee, Mexican Chickadee, Mountain Chickadee, and the Siberian Tit.

Chickadees are found throughout much of North America including Alaska and most of Canada. They are also found on Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Queen Charlotte Island and Vancouver Island. In general, they do not migrate. Every couple of years when populations are high, birds that hatched within the past year may “irrupt” (spread out), or move southward in the fall.

Chickadees get their name from their familiar chick-a-dee-dee-dee song. This simple-sounding call is astonishingly complex. It has been observed to consist of up to four distinct units which can be arranged in different patterns to communicate information about threats from predators and coordination of group movement. Recent study of the call shows that the number of dees indicates the level of threat from nearby predators. In an analysis of over 5,000 alarm calls from chickadees, it was found that alarm calls triggered by small, dangerous raptors had a shorter interval between chick and dee and tended to have extra dees, usually averaging four instead of two. In one case, a warning call about a pygmy owl – a prime threat to chickadees – contained 23 dees.

There are a number of other calls and sounds that Chickadees make, such as a gargle noise usually used by males to indicate a threat of attacking another male, often when feeding. This call is also used in sexual contexts. This noise is among the most complex of the calls, containing 2 to 9 of 14 distinct notes in one population that was studied.

Insects (especially caterpillars) form a large part of the Chickadee’s diet in summer. The birds hop along tree branches searching for food, sometimes hanging upside down or hovering; they may make short flights to catch insects in the air. Seeds and berries become more important in winter, though insect eggs and pupae remain on the menu. Black oil sunflower seeds are readily taken from bird feeders. The birds take a seed in their bill and commonly fly from the feeder to a tree, where they proceed to hammer the seed on a branch to open it.

At bird feeders, Black-capped Chickadees tolerate human approach to a much greater degree than other species. In fact, during the winter many individuals accustomed to human habitation will readily accept seed from a person’s hand.

Have you ever wondered how chickadees, weighing about 12 grams and small enough to fit inside a human hand, can survive winter? They have high metabolic rates and little body fat.

On cold winter nights, Chickadees reduce their body temperature by up to 10–12 °C (from their normal temperature of about 42 °C) to conserve energy. Such a capacity for torpor is rare in birds (or at least, rarely studied). While this may seem counterproductive, “nocturnal hypothermia” probably reduces energy expenditure by as much as ten percent.

As winter approaches temperatures decrease as does the supply of insects, berries and seeds. The birds must eat during the day and put on sufficient fat to be metabolized as heat during the night. Some studies suggest chickadees may gain ten to a whopping 60 percent of their body weight in a day to keep warm through the long winter night. On extremely cold nights, a chickadee uses almost all of its body fat to keep warm, then replaces it the next day in order to repeat the cycle.

To ensure a food supply, during autumn the chickadee roams a territory covering tens of square miles, gathering morsels of food and stores them in hundreds of hiding places in trees behind buckled pieces of bark, in patches of lichens and other caches. In the fall the chickadee’s hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for spatial organization and memory, grows by 30 percent. In the spring, when memory requirements lessen, the chickadee’s hippocampus shrinks back to its normal size,

In the states of Alaska and Washington, and in parts of western Canada, Black-capped Chickadees are among a number of bird species affected by an unknown agent that is causing beak deformities, which may cause stress for affected species by inhibiting feeding ability, mating, and grooming. Black-capped Chickadees were the first affected bird species, with reports of the deformity beginning in Alaska in the late 1990s, but more recently the deformity has been observed in close to 30 bird species in the affected areas, as reported by the Alaska Science Center of the United States Geological Survey.

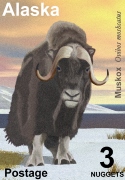

Click on image for full-size view.

The label from a bottle of Chickadee All Natural Birch Beer