Summer in Alaska. It was somewhere around seventy degrees here today. A real scorcher! And the bears are surfing on that cold, cold water.

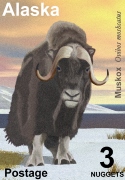

This is from the hottest t-shirt around.

Click on image for full-size view.

Knik Arm and Turnagain Arm. surrounding Anchorage, boast the second highest tides in North America after the Bay of Fundy. These tides, which can reach 40 feet, come in so quickly that they sometimes produce a wave known as a bore tide wave. Adventurous locals have taken to riding this wave out on a kayak or board – talk about extreme surfing!

The best place to see the Alaskan bore tide is along Turnagain Arm, just south of Anchorage. In particular, Beluga Point, Indian, and Bird Point are easily accessible by road and are within an hour drive of Anchorage. Bird Point offers a small interpretive panel dedicated to the tide.

Bore tides exist in other places around the globe such as the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia, and the Tsientang River in China. The longest exists in the Amazon River in South America – there too, extreme surfers dare the wave on a 99-mile stretch of water.

CAUTION! Bore tides are dangerous. Due to the quicksand-like mudflats that make up the beaches along Turnagain Arm, hikers may get stuck in the mud and drown or die from hypothermia. Always stay off the mud flats and observe the bore tide from a safe distance.

The best times to see a good bore are when the low tide in Anchorage has a high negative value, particularly if the good low tide is followed by a large high tide; this maximizes the “sloshing” effect that causes bore tides to occur.

The bore tides are a must-see experience in Southcentral Alaska, as they occur in so few other places in the world. Be sure to enjoy this phenomenon from a safe distance, however, as they can be quite dangerous due to their height and speed of approach in addition to the mudflats mentioned above.

A tidal bore (or simply bore in context, or also aegir, eagre, or eygre) is a tidal phenomenon in which the leading edge of the incoming tide forms a wave (or waves) of water that travels up a river or narrow bay against the direction of the river or bay’s current. As such, it is a true tidal wave and not to be confused with a tsunami, which is a large ocean wave traveling primarily on the open ocean.

Bores occur in relatively few locations worldwide, usually in areas with a large tidal range 20 ft between high and low water and where incoming tides are funneled into a shallow, narrowing river or lake via a broad bay. The funnel-like shape not only increases the tidal range, but it can also decrease the duration of the flood tide, down to a point where the flood appears as a sudden increase in the water level. A tidal bore takes place during the flood tide and never during the ebb tide.

A tidal bore may take on various forms, ranging from a single breaking wavefront with a roller — somewhat like a hydraulic jump — to “undular bores”, comprising a smooth wavefront followed by a train of secondary waves (whelps). Large bores can be particularly unsafe for shipping but also present opportunities for river surfing.

Two key features of a tidal bore are the intense turbulence and turbulent mixing generated during the bore propagation, as well as its rumbling noise. The visual observations of tidal bores highlight the turbulent nature of the surging waters. The tidal bore induces a strong turbulent mixing in the estuarine zone, and the effects may be felt along considerable distances. The velocity observations indicate a rapid deceleration of the flow associated with the passage of the bore as well as large velocity fluctuations. A tidal bore creates a powerful roar that combines the sounds caused by the turbulence in the bore front and whelps, entrained air bubbles in the bore roller, sediment erosion beneath the bore front and of the banks, scouring of shoals and bars, and impacts on obstacles. The bore rumble is heard far away because its low frequencies can travel over long distances. The low-frequency sound is a characteristic feature of the advancing roller in which the air bubbles entrapped in the large-scale eddies are acoustically active and play the dominant role in the rumble-sound generation.

The word bore derives through Old English from the Old Norse word bára, meaning “wave” or “swell”.

Nitinat Lake on Vancouver Island has a sometimes dangerous tidal bore at Nitinat Narrows where the lake meets the Pacific Ocean. The lake is popular with windsurfers due to its consistent winds.

Most rivers draining into the upper Bay of Fundy between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick have tidal bores. Notable ones include:

The Petitcodiac River. Formerly the highest bore in North America at over 6.6 ft; however, causeway construction and extensive silting reduced it to little more than a ripple, until the causeway gates were opened on April 14, 2010, as part of the Petitcodiac River Restoration project and the tidal bore began to grow again.

The Shubenacadie River, also off the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia. When the tidal bore approaches, completely drained riverbeds are filled. It has claimed the lives of several tourists who were in the riverbeds when the bore came in. Tour boat operators offer rafting excursions in the summer.

The bore is fastest and highest on some of the smaller rivers that connect to the bay including the River Hebert and Maccan River on the Cumberland Basin, the St. Croix, Herbert and Kennetcook Rivers in the Minas Basin, and the Salmon River in Truro.

Tidal-bore affected estuaries are the rich feeding zones and breeding grounds of several forms of wildlife. The estuarine zones are the spawning and breeding grounds of several native fish species, while the aeration induced by the tidal bore contribute to the abundant growth of many species of fish and shrimps (for example in the Rokan River).